Climate Data Labyrinth, 2017

Woven dimensions 1.68m x 20m. Installation space varies.

Cotton, linen, mohair, acetate monofilament, rayon, polyester.

Woven dimensions 1.68m x 20m. Installation space varies.

Cotton, linen, mohair, acetate monofilament, rayon, polyester.

Climate Data Labyrinth

Kathleen Vaughan

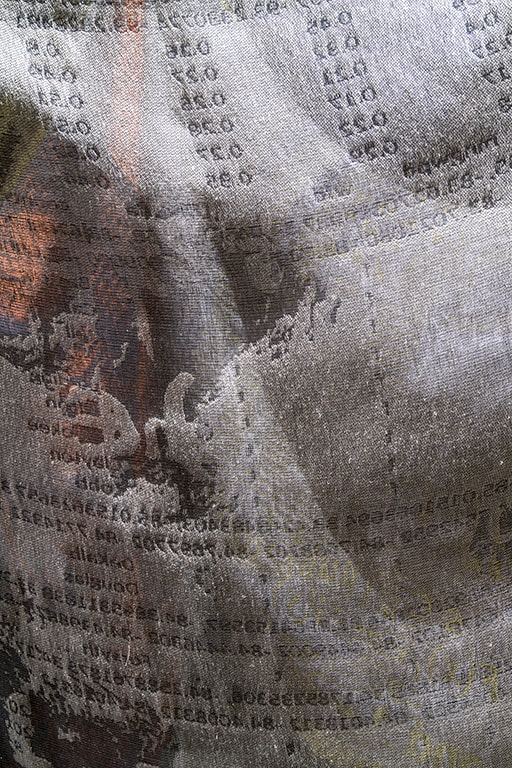

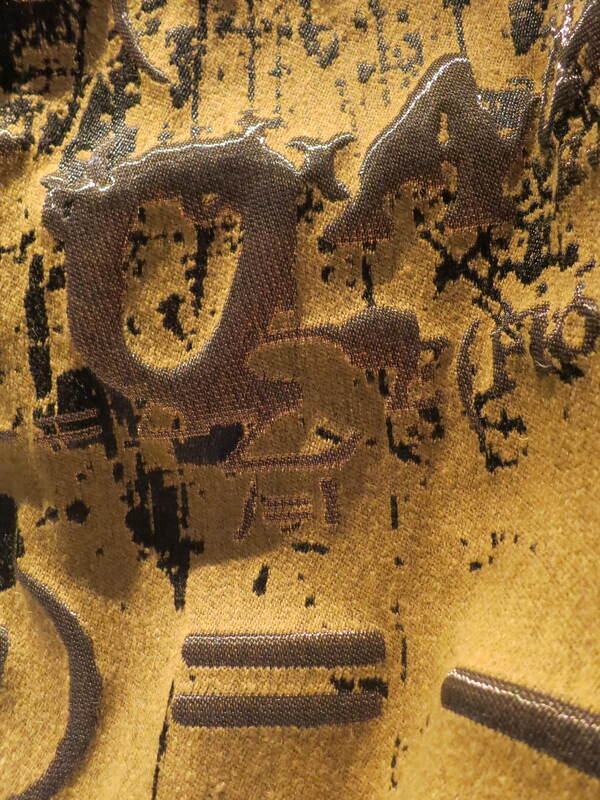

In her Climate Data Labyrinth (2017), Kelly Thompson offers the visitor an enveloping experience that questions our structures of knowledge and communications with particular reference to the single issue that most threatens our survival: global climate breakdown.[1] To create the imagery for her room-scale environmental weaving, Thompson borrows climate scientists’ visual artifacts: mathematical equations, satellite images of landscapes, text – the tools and techniques of climate scientists’ data collection. Images, numerals, symbols, landforms, collaged together and barely recognizable, dance across the multiple surfaces of Climate Data Labyrinth, appear and disappear in cloth layers and folds, peek from pockets, and emerge, partially seen, through surprising transparencies. The layers conjoin and split apart, loll open mouths and undulate tiered folds. We are lost in the convolutions of labyrinthine draping, lost in the confusions of data. The content seems ‘significant’ but is distressingly incomprehensible: how can we understand, negotiate, tease apart and unravel the work’s meanings when it seems that nothing we individually do can actually affect climate shift – no matter how earnestly we each change our behaviours of consumption. The data that Thompson gives us are impossible to read, understand and translate into action or optimism.

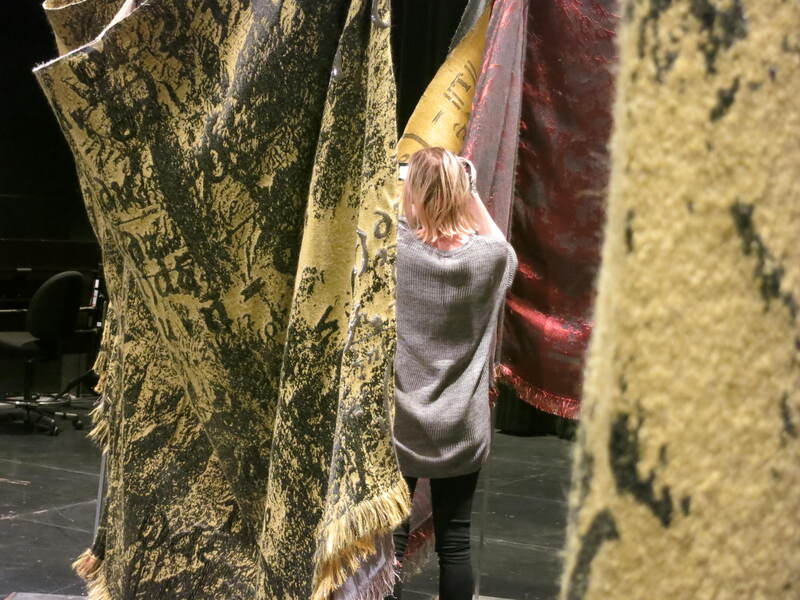

Thompson’s suspended four-layer, woven cloth environment takes the form of an open ring so large – about five metres in diameter – that the full work cannot be perceived in one glance. The visitor must walk around and within the work to begin to encounter the weaving’s content and inner structures, presented in a limited palette of warm tones against grey/black neutrals. Perhaps conscious that 2017 was just about the hottest year on record,[2] Thompson has selected colours of inexorable warming – the heat of burnt orange, an inextinguishable sizzling yellow, the charred carbon of remains. We see in these colours the forest fires that have raged this year across tinder-dry western North America. Integrating rayon, plastics, monofilament, mohair, cotton and linen, Climate Data Labyrinth offers an enticing interplay of both non-biodegradable and natural materials, devastatingly like our own afflicted world.

---

I have been a keen observer of Kelly Thompson’s creative projects throughout the last decade since we both came to Concordia University. Right from the start, she spoke of her intent to create an environmental weaving, an architectural weaving, a weaving that was an object in space rather than artwork on a wall. Climate Data Labyrinth is the realization of this long-standing artistic desire, as well as the mobilization of a much broader artistic and conceptual engagement with questions of big data: data sets that are oriented to understanding large patterns of behaviour, and are themselves so large that traditional approaches to computation break down. To take up these issues, and investigate the connections of digitality that link jacquard weaving and other forms of data assembly and translation, in 2014 Thompson mobilized the Weaving Data Research Group, which provided opportunities for affiliated artists and graduate researchers to investigate together as much as it provided a framework for Thompson’s independent artist inquiry.[3]

In the interval, Thompson has explored the relationship between data and jacquard weaving through multiple artistic projects, using practices both historical and contemporary. At the Lisio Foundation (Fondazione Lisio Arte Della Seta)[4] in 2014, she looked back to 19th century techniques for weaving velvet with punch card technology, digital prequels. Exploring options for manipulating the punch cards beyond their conventional use (via reversals and overlappings), Thompson’s Traces (2014) made contemporary these tools of the past as she wove small velvet works of subtle luxury. In 2015, she worked in digital darkness (without personal online access) as an artist at sea on a container ship traveling between Charleston, South Carolina, and Auckland, New Zealand drawing, stitching and writing the relationships she encountered between the actual transport of goods around the planet, and the digital transfer of navigation and weather data that allowed such trading travel to take place.[5] Her photos from aboard the ship – navigation panels, radar and weather maps, images of the cargo hold, became the basis of large-scale Artist at Sea (2015) weavings she developed at the TextielLab[6] in Tilburg, Netherlands. Using Tilburg’s high-speed commercial jacquard looms, Thompson was able to create weavings larger than those possible on the TIS loom at Concordia University. This hands-on experience with Tilburg’s tools and technicians then made possible the conceptual work and more extensive TextielLab residency required to produce Climate Data Labyrinth (2017).

Complex and large, Climate Data Labyrinth laid flat is 1.7 m in width – or the average height of today’s human male – by 20 metres in length, and is woven of eight weft fibres forming four layers intersecting in multiple ways. A project of collaborative problem solving with the technicians of the TextielLab, the making began with maquettes, structural experiments, yarn choices and sampling of various weave structures, each layer individualized by the choice of threads brought forward or pushed back. Each choice must be planned and programmed before the creation of the cloth begins, every ‘stitch’ – or moment where the weft crosses the warp – determined in advance. Climate Data Labyrinth was a decade in the anticipation, three years in the readying, eight months in specific planning, two weeks in the programming and sampling, and just 16 hours in the actual high-speed automated weaving, a digital magic.

Climate Data Labyrinth arrived in Canada in a person-sized roll, strapped to wheels for mobility. Unwrapped, unfolded, binding edges clipped open, installed, Thompson’s artwork hovers uncannily about two feet above the ground, glowing against the darkness of Concordia University’s Black Box. This is a work of paradox, of great substance that in levitation appears weightless; a still project whose waves and folds suggest movement; a product of desolation and anxiety that in its remarkable virtuosity and material appeal seduces us into believing in human capacity. We look at Thompson’s Labyrinth in hope that we can from among its many layers of woven cloth, find the thread that will lead us out of the dangerous paralysis of data overload, away from the monster of climate change denial, and towards a future of ethical engagement with our beautiful and fragile planet. If artwork like this is possible, perhaps the implications of the climate breakdown it summons will not destroy our planet after all…?

[1] This is the phrase proposed by environmental writer George Monbiot as preferable to ‘climate change,’ which he suggests trivializes the issue and its devastating implications for our planet. See his blog at http://www.monbiot.com/category/climate-change/

[2] In fact 2017 was the second hottest year ever, and the hottest year without a mitigating El Niño effect. The year’s temperatures represented an intensification of the overall global warming trend, as discussed in the Guardian: theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2018/jan/02/2017-was-the-hottest-year-on-record-without-an-el-nino-thanks-to-global-warming

[3] This project, Material Codes, Ephemeral Traces, was made possible by multi-year funding from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture (FRQSC]

[4] fondazionelisio.org

[5] kellythompson.org/artist-at-sea.html

[6] textiellab.nl/en/

Kathleen Vaughan

In her Climate Data Labyrinth (2017), Kelly Thompson offers the visitor an enveloping experience that questions our structures of knowledge and communications with particular reference to the single issue that most threatens our survival: global climate breakdown.[1] To create the imagery for her room-scale environmental weaving, Thompson borrows climate scientists’ visual artifacts: mathematical equations, satellite images of landscapes, text – the tools and techniques of climate scientists’ data collection. Images, numerals, symbols, landforms, collaged together and barely recognizable, dance across the multiple surfaces of Climate Data Labyrinth, appear and disappear in cloth layers and folds, peek from pockets, and emerge, partially seen, through surprising transparencies. The layers conjoin and split apart, loll open mouths and undulate tiered folds. We are lost in the convolutions of labyrinthine draping, lost in the confusions of data. The content seems ‘significant’ but is distressingly incomprehensible: how can we understand, negotiate, tease apart and unravel the work’s meanings when it seems that nothing we individually do can actually affect climate shift – no matter how earnestly we each change our behaviours of consumption. The data that Thompson gives us are impossible to read, understand and translate into action or optimism.

Thompson’s suspended four-layer, woven cloth environment takes the form of an open ring so large – about five metres in diameter – that the full work cannot be perceived in one glance. The visitor must walk around and within the work to begin to encounter the weaving’s content and inner structures, presented in a limited palette of warm tones against grey/black neutrals. Perhaps conscious that 2017 was just about the hottest year on record,[2] Thompson has selected colours of inexorable warming – the heat of burnt orange, an inextinguishable sizzling yellow, the charred carbon of remains. We see in these colours the forest fires that have raged this year across tinder-dry western North America. Integrating rayon, plastics, monofilament, mohair, cotton and linen, Climate Data Labyrinth offers an enticing interplay of both non-biodegradable and natural materials, devastatingly like our own afflicted world.

---

I have been a keen observer of Kelly Thompson’s creative projects throughout the last decade since we both came to Concordia University. Right from the start, she spoke of her intent to create an environmental weaving, an architectural weaving, a weaving that was an object in space rather than artwork on a wall. Climate Data Labyrinth is the realization of this long-standing artistic desire, as well as the mobilization of a much broader artistic and conceptual engagement with questions of big data: data sets that are oriented to understanding large patterns of behaviour, and are themselves so large that traditional approaches to computation break down. To take up these issues, and investigate the connections of digitality that link jacquard weaving and other forms of data assembly and translation, in 2014 Thompson mobilized the Weaving Data Research Group, which provided opportunities for affiliated artists and graduate researchers to investigate together as much as it provided a framework for Thompson’s independent artist inquiry.[3]

In the interval, Thompson has explored the relationship between data and jacquard weaving through multiple artistic projects, using practices both historical and contemporary. At the Lisio Foundation (Fondazione Lisio Arte Della Seta)[4] in 2014, she looked back to 19th century techniques for weaving velvet with punch card technology, digital prequels. Exploring options for manipulating the punch cards beyond their conventional use (via reversals and overlappings), Thompson’s Traces (2014) made contemporary these tools of the past as she wove small velvet works of subtle luxury. In 2015, she worked in digital darkness (without personal online access) as an artist at sea on a container ship traveling between Charleston, South Carolina, and Auckland, New Zealand drawing, stitching and writing the relationships she encountered between the actual transport of goods around the planet, and the digital transfer of navigation and weather data that allowed such trading travel to take place.[5] Her photos from aboard the ship – navigation panels, radar and weather maps, images of the cargo hold, became the basis of large-scale Artist at Sea (2015) weavings she developed at the TextielLab[6] in Tilburg, Netherlands. Using Tilburg’s high-speed commercial jacquard looms, Thompson was able to create weavings larger than those possible on the TIS loom at Concordia University. This hands-on experience with Tilburg’s tools and technicians then made possible the conceptual work and more extensive TextielLab residency required to produce Climate Data Labyrinth (2017).

Complex and large, Climate Data Labyrinth laid flat is 1.7 m in width – or the average height of today’s human male – by 20 metres in length, and is woven of eight weft fibres forming four layers intersecting in multiple ways. A project of collaborative problem solving with the technicians of the TextielLab, the making began with maquettes, structural experiments, yarn choices and sampling of various weave structures, each layer individualized by the choice of threads brought forward or pushed back. Each choice must be planned and programmed before the creation of the cloth begins, every ‘stitch’ – or moment where the weft crosses the warp – determined in advance. Climate Data Labyrinth was a decade in the anticipation, three years in the readying, eight months in specific planning, two weeks in the programming and sampling, and just 16 hours in the actual high-speed automated weaving, a digital magic.

Climate Data Labyrinth arrived in Canada in a person-sized roll, strapped to wheels for mobility. Unwrapped, unfolded, binding edges clipped open, installed, Thompson’s artwork hovers uncannily about two feet above the ground, glowing against the darkness of Concordia University’s Black Box. This is a work of paradox, of great substance that in levitation appears weightless; a still project whose waves and folds suggest movement; a product of desolation and anxiety that in its remarkable virtuosity and material appeal seduces us into believing in human capacity. We look at Thompson’s Labyrinth in hope that we can from among its many layers of woven cloth, find the thread that will lead us out of the dangerous paralysis of data overload, away from the monster of climate change denial, and towards a future of ethical engagement with our beautiful and fragile planet. If artwork like this is possible, perhaps the implications of the climate breakdown it summons will not destroy our planet after all…?

[1] This is the phrase proposed by environmental writer George Monbiot as preferable to ‘climate change,’ which he suggests trivializes the issue and its devastating implications for our planet. See his blog at http://www.monbiot.com/category/climate-change/

[2] In fact 2017 was the second hottest year ever, and the hottest year without a mitigating El Niño effect. The year’s temperatures represented an intensification of the overall global warming trend, as discussed in the Guardian: theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2018/jan/02/2017-was-the-hottest-year-on-record-without-an-el-nino-thanks-to-global-warming

[3] This project, Material Codes, Ephemeral Traces, was made possible by multi-year funding from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture (FRQSC]

[4] fondazionelisio.org

[5] kellythompson.org/artist-at-sea.html

[6] textiellab.nl/en/